In Celebration of the Kibbutz

Beverley Marshal writes of the joy of the kibbutz, and its role in rebuilding a sense of humanity in the shadow of 7.10.

It’s heartening to hear stories of renewal in southern Israeli kibbutzim that were viciously attacked during 7.10. Kibbutz Be’eri has reopened its dining room, which is the heart and soul of kibbutz life. This is a start in Israel’s journey to rebuild itself after the massacre of innocent men, women and children in the south of the country.

The brutality that Hamas showed to those innocent people on 7.10 both at the rave and in southern Israeli communities was beyond evil. Having visited and lived on a kibbutz I found the barbaric attacks on the people of Israel and the destruction of their homes hard to contemplate, given the feeling of community and peace that I experienced in the kibbutzim that I previously lived in, and had recently revisited.

When I was at secondary school studying religious studies, I learned about Judaism, and the kibbutz. Myself and several of my 14-year-old classmates thought the idea of volunteering on a kibbutz sounded wonderful, and we all made a pact that as soon as we were old enough we would go off to Israel to work on one. We loved the idea of working on a farm in the sunshine with other like-minded young people and enjoying a socialist utopia.

I left school shortly afterwards and joined the army of office workers, but I never lost sight of my ambition to volunteer on a kibbutz. When I was 22 years old, I got the chance to take a three month sabbatical from my job and went to the offices of Kibbutz 67 in Finchley Road, who arranged a place for me on Kibbutz Ein HaMifratz in northern Israel.

I arrived at Ben Gurion airport, slightly overwhelmed, carrying a heavy backpack and armed with travel instructions that took me along the Mediterranean, up from Haifa and near to Akko. The scenery was stunning. The kibbutz was very pretty, but the volunteers’ area next to the chicken factory was smelly, dirty, and unpleasant, strewn with old furniture outside the rooms, remnants of smouldering fire-pits, and broken sun loungers littering the place. It was not quite the utopia I had hoped for, and my first job was in the kitchen, where I washed up big pots and pans, from 8am to 2pm, six days a week.

Still, the kibbutzniks were friendly and the volunteers liked to party. I shared a room with another English girl who was dating a kibbutznik, and we would hang out with his friends and the other volunteers in the dining room every breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

On Fridays everyone from the kibbutz would come to the dining room for the Shabbat dinner and it would be the liveliest place–lots of children, young people back from national service, and the elderly, all enjoying the sharing of food and time together.

After dinner all the young people would get ready to go to the pub which only opened on Friday evenings. We’d buy bottles of Goldstar, smoke endless packs of Noblesse, and dance energetically to Nirvana, B52s and all the nineties pop music (with the occasional hippy anthem, like Aquarius from Hair).

The kibbutz had a profound effect on me. I loved the sense of family that I felt when we celebrated Sukkot, Hanukkah, Purim and Independence Day. On these occasions the whole kibbutz would come together. You’d be watching the children perform or be involved in holding candles and singing in the dining room. I also learnt to eat vegetables; I had only ever had tinned carrots and onions before I encountered the kibbutz buffet, with its plentiful salads and–at least to me–unusual vegetables like aubergine.

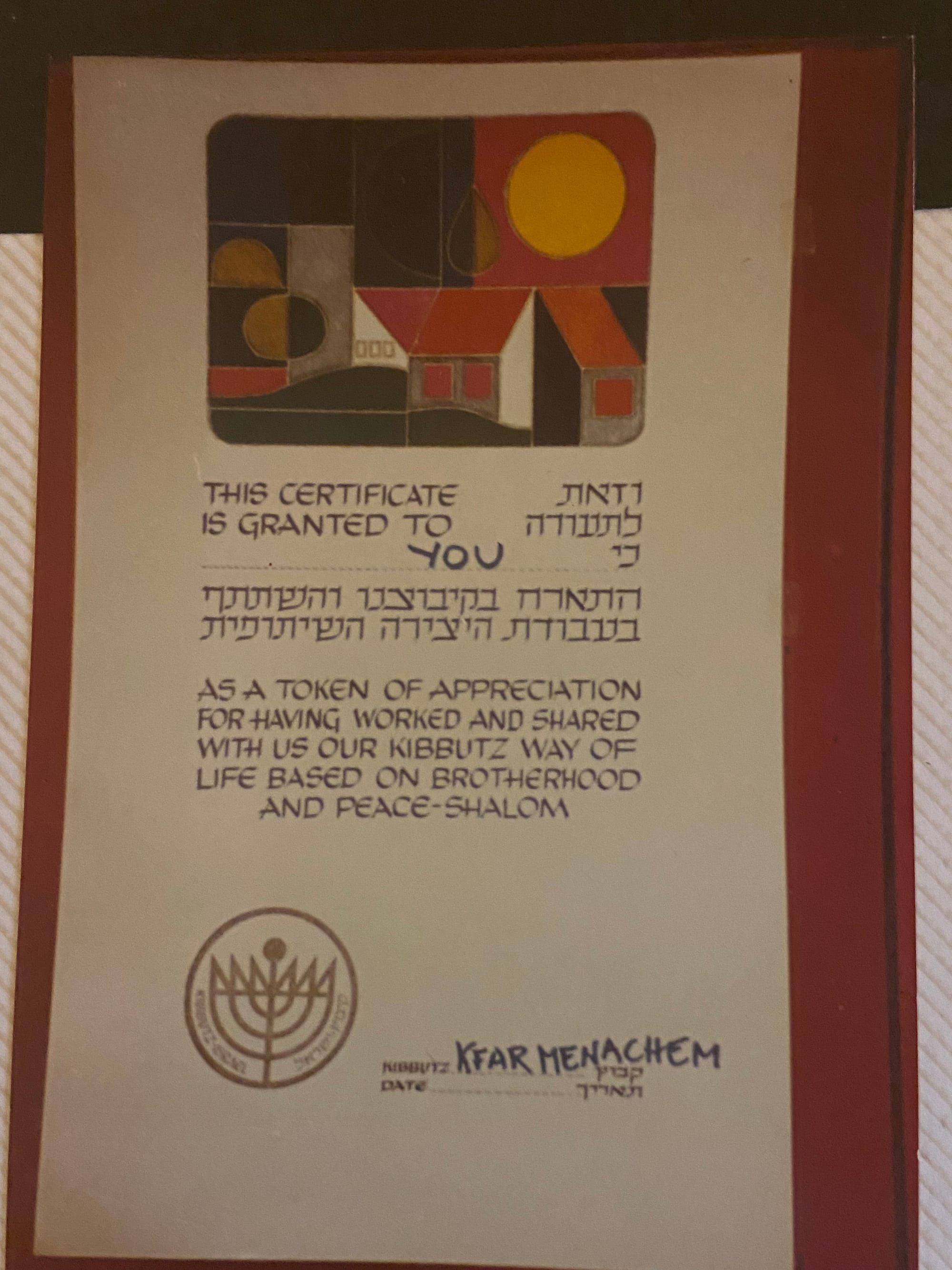

I loved the experience so much that when I came back to the UK a few months later I saved up some money, packed in my job, and went back to Israel to stay on Kibbutz Kfar Menahem near Ashkelon in southern Israel. I lived there for a year and after initially being allocated a job in the metal factory (where I painted red stripes on small pieces of metal, from 7am to 1pm), I ended up establishing myself as chief salad maker with very decent hours. The kibbutzniks I worked alongside showed me great friendship, and invited me to their houses.

In 2019 I took my partner to Israel, and we decided to stay on Kibbutz Ein Gedi for Independence Day, as I knew he’d love the atmosphere and community experience–eating in the dining room and watching all the families enjoy the parade and fireworks.

So, here’s to the southern kibbutzniks who are bravely rebuilding their kibbutzim while the war carries on around them. They shine a light on what is best about humanity, about family, about community. And they demonstrate the importance of standing strong against barbarism.